Thursday, December 20, 2007

Foggy Mountain Breakdown

Friday, December 14, 2007

Let's See How Far We've Come

Thursday, December 13, 2007

The Transparency Incident of 1902- A Poetic and Incongruent Symbol is Born

This is from - http://photontorpedotube.blogspot.com/2007/11/transparency-incident-of-1902.html

by Edwin L. Turnage,

Copyright 2007

"McKissick! Make every shot count!"

Those were the words shouted to future USC President, J. Rion McKissick, who was clutching a pistol, as he and twenty-nine other Carolina students crouched behind a hastily-erected barricade on the Horseshoe in 1902.

On the other side of the barricade, an angry mob of 400 Clemson Cadets, armed with bayonets and swords, threatened bodily harm to the Carolina men and destruction of the South Carolina College. What had enraged the Clemson Cadets to such a degree? Merely the poetic and incongruent symbol of a fighting Gamecock. This was the Transparency Incident of 1902 and it is part of the history of the greatest rivalry in College football, South Carolina versus Clemson.

To understand the context of this armed confrontation between the Carolina and Clemson one must understand the roots and origins of this college football rivalry. The Gamecocks had been playing football from 1895, but to be frank and honest, the early South Carolina football teams were poor. Of course, the school itself was small, not even a University at that time. South Carolina College, which had been stripped of its University status by former Governor Pitchfork Ben Tillman and his political allies in the State Legislature, had only 79 students in 1890. By 1902, it was slightly better; there were just 200 students going to South Carolina College.

Clemson on the other hand, was a much more powerful institution. By and large a creation of Tillmanism, a populist political movement that germinated in South Carolina's turbulent reconstruction era politics. Clemson was a great beneficiary of Governor Pitchfork Ben Tillman's efforts. She was flush with revenue derived from taxes on tobacco, and Tillman, a notorious racist who condoned lynching while governor and later on the Senate floor, ordered African-American prisoners to labor on and improve the campus. Then a military school, Clemson had over 400 student-cadets in 1902.

The two schools began playing football against one another in 1896. Carolina won the first game, 12-6, but Clemson quickly overtook Carolina on the football field, winning the next five meetings. In fact, in those days, Clemson was one of the most powerful football teams in the southeast. In 1900, Clemson's football team was coached by the legendary John Heisman, whose first "Tiger" team went undefeated. The 1900 Tigers also whipped South Carolina by the embarrassing score of 51-0. The defeat was so complete, that the two schools were unable to work out an agreement to play each other on Big Thursday in 1901. (Of course, the Clemson fans claimed that it was because South Carolina College was afraid Clemson would administer another whipping.)

As most serious fans of both schools know, back in those days the Carolina Clemson game was always played on Thursday during the State Fair in Columbia. As part of this event, every year the entire student body from Clemson--its entire Corp of Cadets-- would come to Columbia for the game on Thursday. Afterwards, Clemson's Cadets would remain in Columbia and march in the Elks Club Parade on Friday afternoon.

During the 1897-1900 parades, the Clemson Cadets wore garnet and black colors around their shoes. In this way, Clemson literally dragged the Carolina colors through the dust. Clemson also carried a big bass drum, which a Cadet beat upon as they marched. Inscribed on this drum was a picture of a roaring Tiger with the letters, "S.C.C" (South Carolina College), inside its mouth. This was, obviously, symbolic of Clemson eating up their old rival on the football field.

As a modern-day Gamecock fan, I can easily sympathize with the feelings these indignities must have inflicted on the students and supporters of the liberal arts oriented, South Carolina College. But endure it our people did, in hopes that someday the incredible might reoccur against all odds, a victory over Clemson in football.

Now folks, 1902 was a very special year for the Gamecocks. The school's nickname, "Gamecocks," did not become commonly accepted in South Carolina until 1903 when The State newspaper began referring to the team by that name. However, I'm confident that after you read about the Transparency Incident of 1902, you will agree that the 2002 South Carolina football team truly was the first Gamecock team.

Bob Williams, a Virginian, coached the 1902 football team. Williams still has the best winning percentage of any coach who has ever coached football at South Carolina (overall 14-3). South Carolina College began the 2002 season 3-0. The team would finish the year 6-1. The 1902 football team had a stifling defense. It surrendered just 16 points all season, and it shut out five opponents.

Prior to the Clemson game, the fourth game of the season, Williams hired Christy Benet as his assistant coach. Benet, a former guard on earlier football teams at South Carolina College, was reportedly an inspiring speaker.

Meanwhile, the 1902 Clemson team was clearly a dominant force on the field. The 1902 Clemson team also brought a 3-0 record to the Big Thursday game. Included amongst the Clemson wins was a 60-0 thrashing of North Carolina State, as well as wins over the then very powerful football teams, Georgia Tech and Furman.

Clemson had John Heisman as their coach. The Heisman Trophy is awarded to the best college football player in the NCAA in his honor. Heisman was a noted trick play artist. According to contemporaneous newspaper reports, Clemson was so confident of a victory over South Carolina College on Big Thursday, October 30, 1902, that the Cadets were offering bets with odds of four and five to one. What those over-optimistic Clemson Cadets didn't know was that their Tigers were about to meet the first Gamecock team.

The game itself was described in both The State and The Greenwood Index papers as one of the "prettiest games of football ever played." The Gamecocks jumped to a quick 12-0 lead. The Gamecocks gained the advantage by simple old-fashioned football. They played great defense. Clemson did not get a first down in the first half. Meanwhile, the Carolina offense ground out first down after first down running the ball up through the middle of the line. Thus, the Carolina football team twice marched methodically down the field, running the ball through the middle of Clemson's line. Junior Fullback, Guy Gunter, scored the two touchdowns on short runs. (Touchdowns were only worth 5 points in 1902.) Converting on both extra points, Carolina led 12-0 at halftime.

But this was Clemson. It had a weight advantage, a great football team, and a great coach. In the second half of the game, the Tigers stormed back. First, Clemson scored on a 60 yard trick play run by a halfback named Sitton, an end around play. Then, the Tigers took possession of the ball at the beginning of the fourth quarter and began a determined drive. The drive stalled, however, on the South Carolina 20-yard line, and the Gamecocks took over midway through the fourth quarter. The Carolina offense then proceeded to run out the clock by grinding out first downs through the middle of the Clemson defensive line. Thus, the game ended in a 12-6 Carolina victory.

This was a monumental upset! After such a long victory drought, what joy and happiness this brought to the students and fans of South Carolina College. One football player was quoted in the 1903 Garnet and Black as stating, "Well, Old Pards, how about we just lay down and die right here." Oh, were the South Carolina students were in happy and celebratory.

That is when the transparency arrived, and things got a bit ugly. That Thursday evening, Carolina's students obtained a drawing by F. Horton Colcock, a Professor at South Carolina. The drawing depicted a bedraggled tiger beneath the crowing gamecock. (See a replica of the transparency at the top of this article. This picture was referred to as a "transparency" by the 1902 newspapers.

It was a poetic and incongruous symbol, a proud Gamecock crowing over a powerful feline, the tiger. Perhaps in an era when football teams were typically named after ferocious beasts, it was the unique quality of a Gamecock, crowing over its beaten, apparently stronger foe. The symbolism of Professor Colcock's drawing was beautiful and the liberal arts students at South Carolina fully appreciated its meaning. Thus, on Thursday evening, South Carolina's students began carrying the transparency around Columbia as they celebrated the football victory.

It is not clear what it was about Professor Colcock's image that triggered such a hostile reaction from the Clemson Cadets, but it had a detrimental affect on their minds. Enraged by the Gamecock symbol, the cadets attacked the Carolina students all over Columbia on Thursday night. The State paper reported that in two separate attacks, the cadets destroyed the offensive transparency, and wounded half a dozen Carolina students with sabres, swords and bayonets. The Greenwood Index also reported on the Thursday night incident. "Several students were slightly cut with knives and left the scene with blackened eyes and swollen faces and some scalp wounds made by canes and stones."

As reported in The State newspaper, the Clemson Commandant, Lt. Sirmyer, an Army Officer from West Point, approached the South Carolina Assistant Coach Benet Friday morning after the assaults. Sirmyer warned Benet that the Carolina students would be wise not to carry Professor Colcock's "offensive transparency" in the Parade on Elks Club Friday night. Ominously, Lt. Sirmyer told Benet if the Carolina students did not heed his warning and if they had the temerity to carry that transparency in the parade, he "would not be responsible" for any violence that might ensue. The State reported that after this meeting, "It was openly and repeated stated by the Clemson Cadets that they would break up South Carolina College that night if the transparency was used."

Finding Benet unbowed by his threat, Lt. Sirmyer resorted to political pressure. He went to General Jones, Columbia's Chief of Police, and asked for the Chief to order Benet not to display the Gamecock transparency. Thus, shortly before the parade, Benet met with Lt. Sirmyer and the Chief. Both urged Benet to talk the Carolina students out of displaying their transparency during the parade. The Chief said he saw nothing offensive about the transparency, but he wished to avoid trouble. Benet considered the request, but decided it would be wrong to acquiesce. He told the Carolina students that they must carry the transparency or they would, in effect, reward the whining, political maneuverings, threats, and violence against them by the Clemson representative, Lt. Sirmyer.

Therefore, Carolina students did proudly carry their transparency in the Big Thursday parade. They had earned the right by the football victory. As the Clemson cadets marched by students waving the Gamecock image at them, Lt. Sirmyer urged restraint. At the Capitol where the parade ended, however, Sirmyer told the cadets to "behave like soldiers." Then he added, "while on duty." The amendment to his order was met with cheers by the 400 cadets. Lt. Sirmyer dismissed the Clemson cadets, and retired from the scene. The 400 Clemson boys proceeded straight up Sumter Street toward the Horseshoe, and were, according to Benet's statement published in the paper, "very angry and excited."

Before the approaching Clemson mob arrived at the campus, word reached the Carolina students and they built barricades. The students, including future President McKissick, armed themselves with pistols and repeating rifles. When the 400 Clemson cadets arrived waving their swords, sabers and bayonets, they faced approximately 50 Carolina students behind the barricades. The State paper correctly pointed out that the Carolina students were entitled to protect themselves, and their residences on the South Carolina College campus from the Clemson mob. The State said that most were armed "with pistols and several with repeating rifles."

Fortunately, Benet learned of the approaching Clemson Cadets and he intervened to avert loss of life. Meanwhile, Lt. Sirmyer, the Clemson Commandant and leader who stated he would not be responsible for the bloodshed that resulted from the display of the transparency, was absent.

Recognizing the gravity of the circumstance--one that could easily have led to multiple fatalities--Benet stepped David-like between the two sides and offered to resolve the dispute by fighting any one of the Clemson men that they might choose. When this proposal was not accepted, Benet argued that the two parties should form a committee to arbitrate their differences. By this time, authorities and police began to arrive, and Benet's suggestion was adopted. The Committee decided that the Carolina students would burn the transparency--an image easily reproduced--and Clemson agreed to cheer Carolina, a further humiliation for the Clemson Cadets. This accomplished, the two sides disbursed. Very fortunately, no death or further mahem resulted.

But here the transparency incident did not end. Upon learning news of the incident was reported in The State newspaper, the President of Clemson, P. H. Mell, wrote a letter, justifying the lawless behavior of the cadets. He also argued that Lt. Sirmyer had properly performed his duties, and he implicated Benet and the Carolina students who lacked the "good sense" not to display the transparency.

Clemson's President Mell stated in his letter that the image on the transparency was "too much for them to bear," meaning the Clemson cadets. He argued the violent actions of the Cadets were justified because the City of Columbia had refused to prohibit the Carolina students from displaying the offensive Gamecock symbol in the parade. Therefore, President Mell wrote, the city, "assumed responsibility for the transparency, its intended insult and the results occurring therefrom."

The failure to acknowledge responsibility and recognize that the Clemson cadets had acted lawlessly and breached the peace of the City, provoked a strong and direct response by the Editor of The State, A. E. Gonzales. Gonzales specifically blamed Lt. Sirmyer for the incident. He stated that President Mell should immediately dismiss Lt. Sirmyer as the Commandant of Clemson's Corp of Cadets. "One judges a tree by its fruit," wrote Gonzales. "The fruits of Lt. Sirmyer's actions have been lawlessness and provocation of domestic war."

Please Clemson fans, this November, as the loudspeakers in Williams Brice ring over and over with the beautiful sounds of a Gamecock crowing, do not be bitter or angry. Rejoice with us as we Carolinians celebrate in our victory. Let us celebrate our victory, and please don't get mad at us about our Gamecocks.

Go Gamecocks!

Friday, October 19, 2007

Cell Sin

This past summer I enjoyed some great vacation time with my wife of fifteen years, Grace, and our five children. We went to the high desert and spent most of our time enjoying the sunshine by playing catch, swimming in pools, inner tubing down rivers, going for walks and the like. For the first time in my life, I actually did not turn on my cell phone and did not take any calls or emails while on vacation. I made it a full three weeks of fasting from digital demons such as my BlackBerry, iPod, and second cell phone. Within a few days I also stopped wearing a watch and stopped really caring about time and instead enjoyed my wife, kids, and vacation. In short, it was wonderful. Unplugging my technology and simply having nothing on my body that required a battery seemed like a new kind of spiritual discipline for our age that refreshed and renewed me more than I could have imagined.

Being unplugged from my technology also made me more aware of how much lords over us as a beeping, ringing, and vibrating merciless sovereign god. I was grieved when I went to the pool every day with my kids to swim and play catch in the water and looked around the pool only to see other parents not connecting with their children at all but rather talking on their cell phones and dinking around on their handheld mobile devices while sitting in lounge chairs. When we went out for meals we saw the same thing. Parents with children were commonly interrupted throughout the meal by their technology and spent more time talking on the phone than to their family. To make matters worse, these people were actually quite loud and were incredibly annoying to the rest of us who do not want to hear whether or not their friend Hank’s nasty inner thigh rash had cleared up.

Sadly, the trend continued even late into the evenings. At night my kids like to go for bike rides and walks before heading off to bed so we spent our nights doing just that. At the resort where we stayed, it was amazing how many other families were doing the same, but the parents were not speaking to their children but rather chatting on the phone via their wireless headset (which I keep expecting to include an option to be surgically implanted into one’s head between their ears since there is apparently a lot of extra space there).

A recent article confirmed this is actually a tragic national trend and a cell sin to be repented of. An AP-Ipsos poll found that one in five people toted laptop computers on their most recent vacations, while 80 percent brought along their cell phones. One in five did some work while vacationing, and about the same number checked office messages or called in to see how things were going. Twice as many checked their email, while 50 percent kept up with other personal messages and voice mail. Reasons vacationers performed work-related tasks included an expectation that they be available, a worry about missing important information, or in some cases the enjoyment of staying involved (Source: Associated Press, June 1, 2007, http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/18983920/).

I know in years past I too have been guilty of these same digital sins against God, my family, and my own well-being. Now that I see it as a sin that destroys silence, solitude, fellowship, prayerful listening, and meaningfully and attentive friendship, I am deeply convicted that there is a new spiritual discipline of fasting from technology to be mastered. In this way, we can enjoy the life and people that God puts in front of us rather than ignoring them while we peck away with our thumbs and chat about nothing, which in the end is rarely as important as the people we are ignoring all around us.

Monday, October 15, 2007

Friday, October 12, 2007

"South Carolina comes to Chapel Hill this weekend, and the Gamecocks will descend on us like a plague."

Thursday, Oct. 11, 2007

NO. 7 SOUTH

CAROLINA AT

NORTH CAROLINA

The memories will wash over some of us. Others will be in denial. But there was a time in this state when football was still on a level with basketball and we could dream of 80,000-seat stadiums and national television, a time when the football scores would scroll across the screen of the "Prudential College Scoreboard" and chills would roll across your body as you anticipated the outcome from far-flung places.

They all seem close now, the places that seemed so distant then. Clemson and Athens, Oxford and College Station, Gainesville and Norman. They evoked something that's gone now, replaced by cable and wireless and flat-screen reality. The whole world was flat then, football was king and Columbia, S.C., was hell on earth.

That's all gone now. South Carolina comes to Chapel Hill this weekend, and the Gamecocks will descend on us like a plague. Some of us will see the waves of garnet and black and remember how it could have been. Most of us will have no idea what we're seeing.

Say what you will about South Carolinians and their strange affinity with a game we still struggle to comprehend here north of the border, but the truth is plain and painful to all those who would make this an argument. The uppity Gamecocks are ranked seventh in the nation and will bring a slew of people to Saturday's game, people who understand college football the way we understand basketball, people who back the Gamecocks win or lose, people who hate Clemson more than is healthy and once hated North Carolina the same way.

Well, not quite the same way. The rivalry between Clemson and South Carolina is something we don't have in this state. Take our greatest basketball rivalry, Duke vs. Carolina, and multiply to an unhealthy level and you'll understand the Clemson-USC enmity. Maybe.

After 1971, when South Carolina bolted the ACC in indignation over SAT scores and the perceived bias toward the Big Four schools, a wall was built between Columbia and the state line. Friendships were strained. Longtime relationships ended. Traditions were tossed aside.

Things were never the same again. South Carolina turned its full attention to football, built dorms and decks and shrines to a game that brought attention and expectations and a Heisman Trophy to the Gamecocks. North Carolina lost Bill Dooley, then lost its zeal, eventually paving over prime tailgating areas and building things like hospital wings and classrooms and a big basketball arena.

And then Mike Jordan came to town and football all but died.

Now we watch South Carolina on the flat screen, watch the Gamecocks playing on national television before 80,000 screaming zealots, playing games of national significance in another conference, in another realm. Some of us roll our eyes and mock the energy of a program that wants so badly to win a national title, wants it more than any other program in America.

Now we see them rolling across the highways, flags flapping from black and garnet cars, a devotion to football that we understand only because of our devotion to basketball.

They used to drive up here and complain the whole way. There was no good way to get from Columbia to Chapel Hill.

The kids would come in on Friday night, and Franklin Street would be raucous as student bodies from North and South Carolina partied the way football rivals used to party in this state. Then on Saturday morning, the multitudes would walk through the pines to a beautiful football stadium and renew a rivalry that dated to 1903.

This weekend, the rivalry will resume after pausing for the better part of a generation. The schools haven't met since 1991, the year South Carolina joined the Southeastern Conference and ended any dream that the Gamecocks could return to the ACC and rejoin the league it so naturally fit.

That can never happen now. Too much has happened in the interim, too many friendships strained, too many relationships ended, too many walls built. North and South Carolina parted ways in 1971, the Tar Heels chasing basketball dreams and the Gamecocks chasing a football dream that has brought them more pain than we can ever imagine.

But that's what we always loved and hated them for. Even their basketball teams played tackle in those days.

In 2000, the Gamecocks played a home game against New Mexico State that attracted little attention outside Columbia. It was the first game of the season, so no one else in the nation noticed. They won 31-0. The kids tore down the goal posts that night. They had lost 21 straight games, and yet 81,000 people were inside Williams-Brice Stadium.

Big-time college football is coming back to Chapel Hill this weekend. South Carolina is coming to town.

Wednesday, October 10, 2007

Norwood gives a health to Carolina...

Saturday, October 6, 2007

Friday, September 28, 2007

Thursday, September 27, 2007

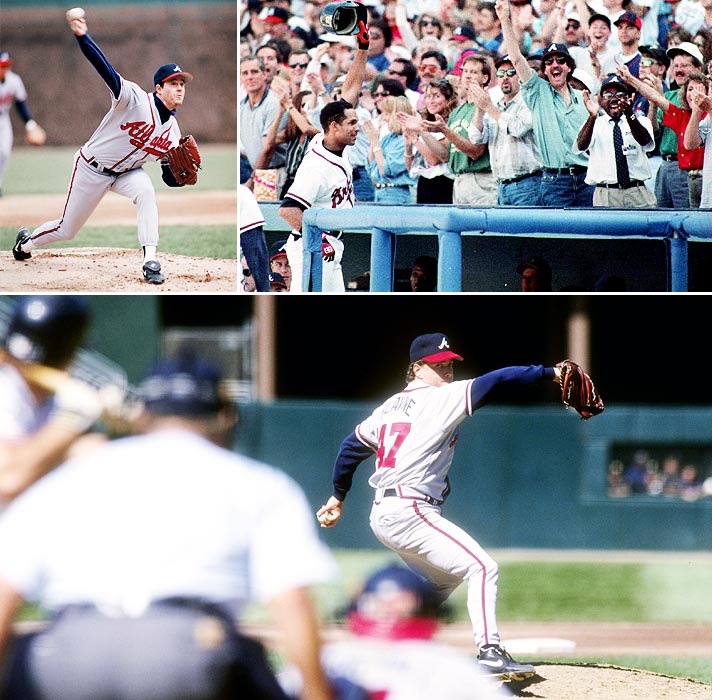

An Atlanta Braves Season to Remember

Every season when the trade deadline approaches, Fred McGriff's name is invoked as the sine qua non of midseason deals. The acquisition came about mainly because the San Diego Padres, for whom McGriff had slugged 35 homers in 1992, fell apart after a strong third-place finish a year earlier. Drifting at 20 games under .500, the Padres decided to unload all their expensive pieces, including Greg Harris, Gary Sheffield and their first baseman, who was making $4.25 million. "I'm dangling out there, I know I'm going somewhere," McGriff told reporters. "I just hope it's to a team in a pennant race."

Every season when the trade deadline approaches, Fred McGriff's name is invoked as the sine qua non of midseason deals. The acquisition came about mainly because the San Diego Padres, for whom McGriff had slugged 35 homers in 1992, fell apart after a strong third-place finish a year earlier. Drifting at 20 games under .500, the Padres decided to unload all their expensive pieces, including Greg Harris, Gary Sheffield and their first baseman, who was making $4.25 million. "I'm dangling out there, I know I'm going somewhere," McGriff told reporters. "I just hope it's to a team in a pennant race."

Cue the theme from "Gone with the Wind." Braves general manager John Schuerholz had a prospect the Padres coveted, Melvin Nieves.

"We knew McGriff was the guy we wanted, and when we were willing to include Nieves, it came together," Schuerholz recalls. "Nieves was a big, strong kid, and a switch-hitter, too." Schuerholz tossed in two other minor leaguers, Donnie Elliott and Vincent Moore (who managed 31 major league games between them), and McGriff was a Brave. Giants GM Bob Quinn spoke for most of baseball when he said: "What bothers me is that San Diego didn't get more for him."

The trade was consummated July 18. Two days later, McGriff arrived for his first game in Atlanta. A roaring bonfire greeted him -- but this was no pep rally. Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium was ablaze.

Braves' radio broadcasters Matt Stewart, Pete Van Wieren and Don Sutton had a close-up view. "We noticed flames coming out of a booth belonging to radio sponsors, about three or four booths down," Stewart says. "A breeze had blown some sterno flames into curtains that had probably been there since the stadium opened in 1965. They went up like pine straw. Sutton grabbed us both and said, 'We gotta get out of here.' "

The fire quickly spread out of control. "Nobody could get in there, because the key was with the owner," Van Wieren says. The press room was evacuated. "We ran away from this thick black smoke, and like dummies got in the elevator," Stewart continues. "When we got to the field, I met Jane Fonda for the first time. She was there with Ted Turner. Suddenly, there was a huge boom, and I jumped 10 feet out of my skin. It was the same thing that happened in the [World] Trade Center on 9/11 -- the steel girders had melted from the heat, and the structure collapsed."

Mark Lemke was standing with fellow infielder and good buddy Jeff Blauser on the field when the blaze erupted. "We were just watching the flames, and suddenly there was a huge boom, and we went tearing out into center field," Lemke said. A photo of the two gazing in disbelief as the press box burns is in the Hall of Fame. Sid Bream, the Braves' first baseman who was about to lose his job with the arrival of McGriff, said of the blaze, "I know I'm the most likely suspect, but I swear I didn't do it."

"Ted Turner told me two things," Schuerholz remembers. "One, 'We're going to play this game.' We cordoned off a portion of the stands for the media -- we didn't have many fans that night -- and started about 90 minutes late. Then he said, 'The stadium's caught fire -- tonight, so will the Braves.' "

As with cable news and the mainstreaming of the buffalo burger, Turner had seen the future with unusual clarity. The Cardinals took a 5-0 lead, but McGriff smashed a long homer to tie it, and Atlanta scored three in the eighth to win. Nine-year-old Jeff Francoeur, now playing right field for the team, was watching at home in suburban Atlanta: "I remember that like it was yesterday. McGriff got here, and suddenly we were sure we would win it."

But for the vagaries of travel, McGriff might have caught fire ... literally. "He was supposed to be [in the flambéed press box] for a news conference," Van Wieren recalls. "Whenever a new player arrived, he was brought upstairs for questions. But his plane was late, and he got to the park just in time for the game. He was told about it afterward, and he just kinda rolled his eyes."

But for the vagaries of travel, McGriff might have caught fire ... literally. "He was supposed to be [in the flambéed press box] for a news conference," Van Wieren recalls. "Whenever a new player arrived, he was brought upstairs for questions. But his plane was late, and he got to the park just in time for the game. He was told about it afterward, and he just kinda rolled his eyes."

The Crime Dog's impact was immediate and telling. He hit .422 with seven homers and 12 RBI in his first dozen games in Atlanta. "It balanced our offense," Schuerholz says. "The pressure was off hitters like [David] Justice and [Ron] Gant, who were trying to pretend they were cleanup hitters."

McGriff was pleasantly surprised by how loose the Braves were. "The first day I got there, they were playing putt-putt in the clubhouse." Two days after McGriff's arrival, the Braves lost to fall a full 10 games behind, but they ripped off their next six to announce they were back in the race.

Baker is still steamed about being misquoted in the wake of the deal. "I said 'I hope they got Fred too late,' but someone left out the word 'hope.' It went out everywhere like I was being cocky, but it was just a misprint." Sadly for Dusty, the Braves used the perceived slight as fuel for their run.

A less-remembered key to Atlanta's turnaround was the replacement of Mike Stanton as closer. Greg McMichael, a rookie who thought his career was over after several knee operations and his release by Cleveland, took over the role and immediately flourished. "His best pitch was a great changeup, and that eliminated lefty-righty matchups, because he could get either out with it," says Mazzone, then the Braves' pitching coach. McMichael was so effective in the late innings that he was featured in Sports Illustrated -- unfortunately, the accompanying photo was of Maddux.

The Giants attempted to make an impact deal at the deadline, too, but balked at Montreal's asking price for aging but cagey starter Dennis Martinez. The Expos wanted a top pitching prospect named Salomon "The Prophet" Torres. Unfortunately for Quinn, he didn't live up to Torres' nickname or he would have pulled the trigger.

The Efficacy of Prayer by C.S. Lewis

January 1959